I have only one reason to write novels, and that is to bring the dignity of the individual soul to the surface and shine a light upon it. The purpose of a story is to sound an alarm, to keep a light trained on The System in order to prevent it from tangling our souls in its web and demeaning them. I fully believe it is the novelist's job to keep trying to clarify the uniqueness of each individual soul by writing stories - stories of life and death, stories of love, stories that make people cry and quake with fear and shake with laughter. This is why we go on, day after day, concocting fictions with utter seriousness.Some more Murakami, from one of my favorite stories of his, "On Meeting the 100% Perfect Girl One Beautiful April Morning":

After talking, we'd have lunch somewhere, maybe see a Woody Allen movie, stop by a hotel bar for cocktails. With any kind of luck, we might end up in bed.Excited for the American publication of 1Q84, which happens Tuesday. Excerpt from the beginning at Asymptote:

Potentiality knocks on the door of my heart.

Now the distance between us has narrowed to fifteen yards.

How can I approach her? What should I say?

"Good morning, miss. Do you think you could spare half an hour for a little conversation?"

Ridiculous. I'd sound like an insurance salesman.

"Pardon me, but would you happen to know if there is an all-night cleaners in the neighborhood?"

No, this is just as ridiculous. I'm not carrying any laundry, for one thing. Who's going to buy a line like that?

Maybe the simple truth would do. "Good morning. You are the 100% perfect girl for me."

No, she wouldn't believe it. Or even if she did, she might not want to talk to me. Sorry, she could say, I might be the 100% perfect girl for you, but you're not the 100% boy for me. It could happen. And if I found myself in that situation, I'd probably go to pieces. I'd never recover from the shock. I'm thirty-two, and that's what growing older is all about.

How many people could recognize Janáček's Sinfonietta after hearing just the first few bars? Probably somewhere between "very few" and "almost none." But for some reason, Aomame was one of the few who could.Other excerpt from 1Q84, from a few months ago in The New Yorker (entitled "Town of Cats"), which I loved:

Tengo, by contrast, was curious about everything. He absorbed knowledge from a broad range of fields with the efficiency of a power shovel scooping earth. He had been regarded as a math prodigy from early childhood, and he could solve high-school math problems by the time he was in third grade. Math was, for young Tengo, an effective means of retreat from his life with his father. In the mathematical world, he would walk down a long corridor, opening one numbered door after another. Each time a new spectacle unfolded before him, the ugly traces of the real world would simply disappear. As long as he was actively exploring that realm of infinite consistency, he was free.

While math was like a magnificent imaginary building for Tengo, literature was a vast magical forest. Math stretched infinitely upward toward the heavens, but stories spread out before him, their sturdy roots stretching deep into the earth. In this forest there were no maps, no doorways. As Tengo got older, the forest of story began to exert an even stronger pull on his heart than the world of math. Of course, reading novels was just another form of escape—as soon as he closed the book, he had to come back to the real world. But at some point he noticed that returning to reality from the world of a novel was not as devastating a blow as returning from the world of math. Why was that? After much thought, he reached a conclusion. No matter how clear things might become in the forest of story, there was never a clear-cut solution, as there was in math. The role of a story was, in the broadest terms, to transpose a problem into another form. Depending on the nature and the direction of the problem, a solution might be suggested in the narrative. Tengo would return to the real world with that suggestion in hand. It was like a piece of paper bearing the indecipherable text of a magic spell. It served no immediate practical purpose, but it contained a possibility.Brief aside recalling somebody, I can't remember who or where, nicknaming Murakami translator Jay Rubin "Clichetown." (Ah, it was a question on Tao Lin's formspring account.)

Brief Q+A up at The Atlantic with Murakami translator Phillip ("Non-clichetown"?) Gabriel:

Did Murakami resist or revise any parts of your translation?

At one point Jay, Murakami, and I got into the question of the nickname of one of the cult's security detail. I originally called him "Skinhead," thinking of a menacing right-wing figure, but Jay preferred "Buzzcut." Murakami said he liked the latter—the military connotations it carried—so that's what we went with.Here, in this past Friday's NY Times, Sam Anderson profiles Murakami:

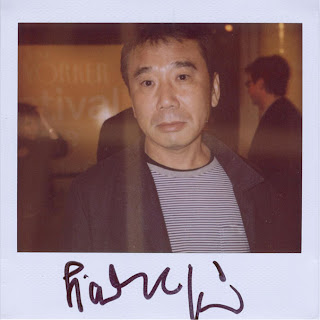

I asked Murakami, whose work is so often dreamlike, if he himself has vivid dreams. He said he could never remember them — he wakes up and there’s just nothing. The only dream he remembers from the last couple of years, he said, is a recurring nightmare that sounds a lot like a Haruki Murakami story. In the dream, a shadowy, unknown figure is cooking him what he calls “weird food”: snake-meat tempura, caterpillar pie and (an instant classic of Japanese dream-cuisine) rice with tiny pandas in it. He doesn’t want to eat it, but in the dream world he feels compelled to. He wakes up just before he takes a bite.

3 comments:

This is an absolutely wonderful post.

Thanks, Rosebud.

I should add this to it, from the Guardian's profile of Murakami that went up last Friday:

"His habit of repetition, whether a stylistic tic or a side-effect of translation from the Japanese, has the effect of making everything Murakami says sound infinitely profound. He has written about the metaphorical importance of his running; that to complete an action every day sets a kind of karmic example for his writing. "Yes," he says. "Mmmmm." He makes a long contemplative sound. "I need strength because I have to open the door." He mimes heaving open a door. "Every day I go to my study and sit at my desk and put the computer on. At that moment, I have to open the door. It's a big, heavy door. You have to go into the Other Room. Metaphorically, of course. And you have to come back to this side of the room. And you have to shut the door. So it's literally physical strength to open and shut the door. So if I lose that strength, I cannot write a novel any more. I can write some short stories, but not a novel."

Nice compilation. Thanks!!

Post a Comment